UK Age Pyramid Now and in 2030. Source: ONS, National Population Projections, 2010-Based Statistical Bulletin, 26 October 2011.

We should envy the UK for having the House of Lords! For they have given us a useful reminder of the consequences of an ageing society. But, like most such analyses, they have ignored one important demographic prediction, and that is the likely trends in the cost of labor.

It’s usually worth listening when the House of Lords takes up an issue. Just think of it: It’s made up of people who are (and aware that they are) (a) at, or past, the epitome of their political and public careers, (b) left with quite a bit less time on this planet than the average citizen, and (c) extremely unlikely to lose their jobs. For all these reasons, when they take up an issue that no-one asked them to look at, it may be worth listening. It’s likely to be

- More Important than the day-to-day political noise

- Uncomfortable for persons who stand for periodic elections

- Crossing party-political lines

These Lords have taken it upon themselves to opine on the issue of demographics, a pet subject of mine and of this blog.

Here is a summary of what they say (the full text, entitled “Ready for Ageing?”, can be looked at here):

Between 2010 and 2030:

- The number of 85-year olds and above will more than double

- 10.7m people will have inadequate retirement income (that’s about half the retirees)

- The number of people with dementia will increase by 80%

To make a success of these demographic shifts, major changes are needed in our attitudes to ageing. Many people will want or need to work for longer, and employers should facilitate this. Many people are not saving enough to provide the income they will expect in later life, and the Government must work to improve defined contribution pensions, which are seriously inadequate for many.

[…]

people can outlive their pensions and savings, suffer ill health and need social care. The Government cannot carry all these risks and costs, but there is much the Government can do to help people prepare

… followed by stuff that’s quite common to such analyses: Reforming pensions and savings, and associated education of the public, home equity release schemes for the elderly, pressures on healthcare and social care, inter-generational equity, etc.; All topics which in themselves are important and well worth spending time on.

But here is what this blog tells you that the House of Lords does not: First, one very important and direct consequence of demographic trends is buried deep in the Annexes of the House of Lord statement, and important details are barely mentioned even there:

The number of children being born is, and has been, going down! This means the supply of labor is going down, unless we increase immigration. But the government has this to say:

‘We will continue to work hard to bring net migration down from the hundreds of thousands to the tens of thousands by the end of this Parliament and to create a selective immigration system that works in our national interest.’

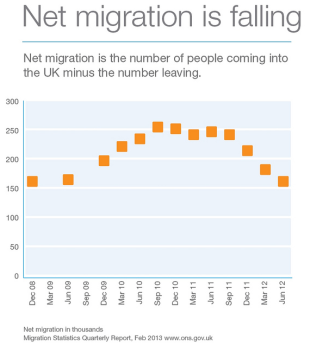

And they have done a “great” job so far: Immigration rates have decreased from about 250,000 p.a. to 150,000 p.a. in the space of one year!

This means there is not only an increase in the elderly driving higher dependency ratio, it is also a decrease in the working population. So just when we need the number of workers to go up in healthcare and social care, the supply is down, leading to inevitable wage pressure, not just from the increased demand alone!

The other thing that isn’t spelled out in any analysis I have seen, including the House-of-Lords paper, is that the old-age-dependency ratio is not just going to be felt in a relative shortage of workers which can be fixed by people saving more so that they can afford them. It has fiscal and monetary knock-on effects.

Allow me to interject, by the way, the reason I am so obsessed about demographics: It is that one can’t argue with it. You can doubt climate change, but you can’t doubt that in 30 years’ time it’s too late to give birth to 30-year old people. They have to be born now. Simple. So, back to these inevitable facts:

The fiscal effects of a decreasing workforce having to shoulder the same or increasing debt service means that, on a per-head basis, people would have to pay higher taxes just to service today’s social care and health care costs and cost of debt financing. However, all of these costs are going up at the same time while the number of workers/taxpayers is going down. It is a quadruple whammy pre-programmed to happen with inescapable certainty: The social care and health care costs are going up because more people enjoy longer healthy lives, as well as longer periods of infirmity. The fiscal costs will go up because in the long term, interest rates, and therefore the cost of servicing the national debt, are unlikely to stay at the low level where quantitative easing has driven them, unless we go into perpetual monetary financing of fiscal policy, which would in any case lead to even higher inflation than the demographically driven wage inflation we predict here.

The demographic pressures can be summed up thus: The cost of labor is going to out-pace the returns on financial capital, and very rapidly indeed. And a lose monetary policy has at best no effect on that trend.

The study by the House of Lords was phrased as a question “Ready for Ageing?”. The report, already pessimistic in its outlook, has ignored important compounding effects which make the reality even worse. So the answer has a resounding: No, not at all.

It’s hard to see how the numbers could be lying: an increasing proportion of elderly and infirm placing an increased financial burden on the revenue base which is in turn being diminished by a decreasing pool of tax payers. Given that it’s already far too late (unless I’ve missed something) to rectify the retirement income problem, I suppose we have to look at the problem from the infirmity angle. It doesn’t seem to help by making the old healthier – one way or another they’ll continue to drain resources by living longer or persisting in employment, thus denying it to the young. I suppose all the more fit and less unhealthy oldies could be employed in the care industries, but I can’t escape from the thought that there will be an increasing number of elderly, infirm people who will be utterly miserable and simply waiting to die. (And I say this as one whose entry to the ranks of the retired is expected in the not-too distant future). I note that the Commission on Assisted Dying proposed in 2012 a legal framework for assisted dying – I suspect it’s only a matter of time before the something passes into law.

LikeLike

In reality, unemployment is high (double-digit in the Eurozone!) wages are falling, and computers and the Internet are replacing millions of jobs. So I reckon the cost of labour is going down, not up.

LikeLike

Paul, of course you are right in this part of the cycle. But when the majority will need care, affordability will still be low, regardless of where in the cycle we are at that time. The subject of my post is a seminal trend and not part of the cycle. The cost of labor will outstrip the cost of capital, and return on human capital will be greater than the return our generation can make on its savings.

LikeLike